Prologue:

I’ve thought about Kilimanjaro everyday since I left it’s slopes, but haven’t been able to find my voice in telling its stories.

It’s hard to put into words something so big and profound, especially when you feel paralyzed in the wake of it.

Coming back from the mountain was almost as challenging as the climb itself – nothing in my daily life felt as important or relevant or exciting. It was like now that I knew this intense feeling of being alive, everything else was inconsequential.

I’d try to explain THIS THING, THIS MOUNTAIN as best I could, but too much had happened; the details became suffocating and I could never find the words to properly articulate the experience.

So I let it sit week and week, trying to figure out how to put it into words – then I wrote thousands upon thousands of words that somehow just didn’t feel right. (As a writer, this was disappointing, surprising and stirred up an awful lot of self doubt. I mean, really? This is what I do and I just can’t get it right).

And the words still don’t feel quite right honestly. But this is my best attempt, at long last, to put the experience into words. To capture the insanely rewarding week I spent on Africa’s highest peak.

I’ve decided to focus on the summit push – the hardest day of the climb, the day that tested me in every way possible.

To say it pushed my limits is somehow hyperbolic and simultaneously a woeful understatement. Have I been through shit that was more challenging than this? Yes. But was it the single most mentally, physically, and emotionally demanding day I’ve ever had? Yes.

And it was also the day that drinking mango juice made me cry. No joke.

____________________

It only took about an hour for my Camelback hose to freeze solid. And it took me awhile to realize it. I would decide to take a drink, steady my feet and mentally prepare to suck the hose’s mouthpiece as hard as I could.

But no water came out, and I was left gasping for breath. It was just after 1am and every movement took an excruciating amount of focus and mental capacity.

Each tiny step forward was calculated. By that point, I could scarcely feel my feet – they became a completely unreliable source for confirming that I was actually touching the ground. I had to look down, to see my legs moving, to will each step.

My world became the two feet radius around me, cast by the glow of my headlamp.

There was nothing beyond this halo of light for me – this was my world. And it was hell.

A literal hell on earth.

I had to keep telling myself to push forward, to draw breath (shallow and labored though it may be), to focus, and to remember that I chose this. I was on a vacation of my choice. I wanted to do this.

But in the moment, I wanted to be anywhere else. Wanted it to be over. Wanted to be warm. Wanted a full breath. I questioned why I had wanted to do this thing at all.

____________________

After four days of hiking 6-10 hours per day, we were bearing down on the summit push; the night we’d been working towards.

We arrived at summit basecamp (15,000 feet) in the late afternoon, ate dinner, had a briefing with our guides and went through a health check. The long days on the trail, coupled with the altitude, left us exhausted as we collapsed into bed at 7pm.

Sleep was elusive though. Maybe it was nerves or excitement. Or maybe it was the thin air that robbed us of sleep. I wanted to pop an Ambien, but I knew I had far fewer than the recommended eight hours to sleep.

In fact, I knew I had only about four hours to potentially get some shut eye. The summit day wake up call was coming at 11pm.

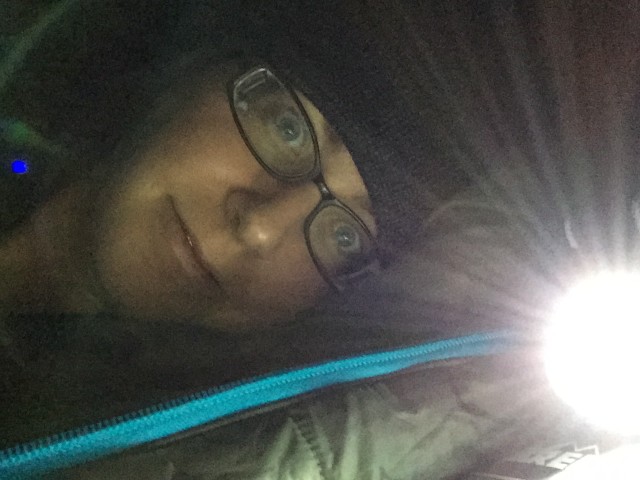

I dozed off and slept restlessly, wrapped in layers of clothing; a cocoon of down sleeping bag with only my nose peeking out into the cold air inside my tent.

And then I heard it, the porter’s light tapping on the side of my tent.

“Dada’s (sisters) time to wake up. Get ready!”

Had I slept at all?

We’d slept (?) in our hiking gear so that all we had to do was groggily grab our packs and head to the mess tent for breakfast – porridge, cookies and tea.

I wore my glasses for the first time on the trek after having been told that it was impossible to wear my contacts to the summit – it was too cold and they would freeze to my eyes.

What. The. Fuck. I didn’t even know such a thing was possible. It was then that I started to really get nervous.

It was midnight when we received a few final words from our guides, stepped out in the bitterly cold night and began a slow march into the darkness.

All we knew was that we had to keep putting one foot in front of the other, no matter how difficult a task that became.

I should mention that there are only three rules on Kilimanjaro, and they had been drilled into our heads the entire climb:

- Listen to your guides

- Pole Pole (slowly slowly)

- Sippy Sippy (drink all your water everyday)

We dutifully followed our guides. It didn’t take long for it to feel like a death march; we had no concept of where we were going or what was around us, we just followed unquestioningly with our heads down.

How our guides knew where they were going is just one of the mysteries of the mountain I have yet to understand. There was no trail or path, no signs, no cairns, they just knew the way in the pitch black.

Within an hour, everyone fell silent and everything felt frozen; limbs, face, body – but especially hands and feet. They were bricks that constantly needed to be checked on.

Hands still holding my trekking poles? Check. Feet still moving forward? Check.

Aside from the freezing cold, the black, the lack of oxygen, and the headache caused by the altitude, it was the wind that was the most cruel element. Gale-force gusts swept across the side of the mountain with relentless ferocity.

Vicious billows knocked us around, often dismantling our single-file line. We had to watch out for each other and help one another back into line when the wind blew one of us aside. All the while, we had no idea if we were next to a sheer cliff-face or an outcropping of rocks.

It was the blind leading the blind through a cyclone. (We found out later that the winds that night were the strongest the mountain had seen in years – lucky us?)

Even though I was wearing multiple pairs of pants and more top layers than I ever had at one time in my life (long johns, a long-sleeves shirt, an Oregon Ducks tee shirt, a down coat, a down vest, a windbreaker and a ski shell), I was still chilled to the bone.

Time became an afterthought somehow, an analogous concept really. And something I simply didn’t allow myself to think about. It was too awful and depressing to dwell on – 6 more hours until sunrise, 5 more hours, 4 more hours.

Instead of thinking about time, I thought about what the beach in Zanzibar would feel like; sand underfoot, the tide lapping my ankles, hair sweeping across my face from a gentle breeze.

I thought of nights curled up on the couch cuddling – how warm and cozy and simple those moments were. All I could feel now were the hurricane-force winds lashing my cheeks, stinging my eyes. Tears froze to my cheeks as they fell.

And I thought about Annie and Bobbi Jo, my friends on this god-awful ascent. They very well could hate me for this – this was my idea, this moment indirectly my doing. I might lose friends over this and I wouldn’t blame them one bit.

When the wind paused a moment, I would look up to the skies, so full of brilliantly bright stars. More stars than I had seen since nights spent in the remote isolation of Mongolia’s Gobi Desert.

I’d never been so close to the stars with my feet still on the ground (literally).

Some stars were so bright I felt as though I could reach out and touch them; hold the infinite in my hands. And then it donned on me…these weren’t stars at all. These lights, in horrific fact, were the headlamps of the other climbers ahead of us.

They weren’t stars and I had to go to there – I actually had to go that high up. It seemed impossible and I hated myself for that moment of clarity. Ignorance had been a cosmically romantic bliss.

I felt desperate for an alternative truth, but the only truth was that I was freezing on the side of a mountain and I had to keep moving forward.

Even with all of these thoughts racing through my head, there was nothing; time disappeared.

Minutes felt like hours, yet hours just slip away. It was an instant, a forever eternity.

There was a constant flux between being in total awe of what I was doing and where I was, and wanting to lay down and cry and be anywhere else besides the side of this brutal mountain.

Then, just when I was really starting to hate everything, I looked up and saw color in the sky. Color! Not black! The sun was about to break the horizon. My happiness and exuberance were unfathomable.

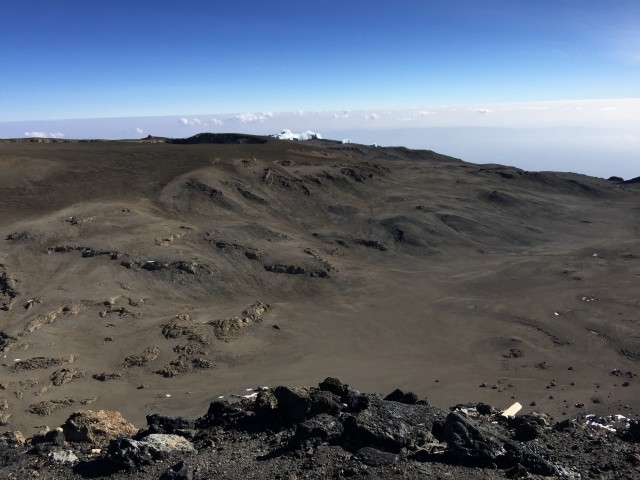

Minutes later came a moment of pure joy; the sun hit my face, the wind stalled for a moment and I looked out on to an alien landscape of black earth for the first time.

It was another hour of hiking before we reached Stella Point (18,885ft) to take a much needed rest.

Our guides were all smiles and jokes – we were beaten down monsters. But one of our summit porters pulled a thermos of tea out of his pack and by some small miracle its contents were still hot!

We each savored a half a cup of heaven as we caught our breaths.

How the tea managed to still be warm after seven hours in those conditions was truly miraculous. I mean serious mountain magic.

For reference – I pulled my Nalgene bottle out of my pack and it was nearly frozen through. The Snickers bar that I’d foolishly been longing to eat for hours, was also frozen; so hard and dense it could have been used as a weapon.

That tea was pure joy.

After our break, there was another hour of mountain ahead of us. But this section was easier for many reasons; we caught a burst of energy, there was daylight, it was a bit warmer, the incline was less severe, we could see where we were going, and we had the knowledge that this ordeal was nearly over…or so we thought.

Annie, Bobbi and I set off with a guide ahead of some others in our group and pushed on. For the first time in hours, we spoke. Or rather we coughed up words at one another, our faint voices trying to be heard over the howl of the wind that continued to blow us around like tattered prayer flags.

This last bit to reach Uhuru Peak took us along the rugged rim of the mountain’s volcanic crater, a vast expanse of black rock.

My skull was pounding from an altitude-induced headache and I tried to remember what it felt like to take a full breath.

My attention was fully focused on the ground and the crater to my right. That was until I dared to look left. I stopped cold and stood staring with mouth agape. A massive glacier seemed to be suspended in the air – it was black pumice earth, bright glacier and sky.

I can honestly say that I have never seen anything quite like it. It didn’t seem real that such a thing could exist. My wind-chapped lips couldn’t help but curl into a painful smile.

Our feet carried us still higher until we caught our first glimpse of the iconic summit sign of Uhuru Peak. The sign that we’d longed to see for days on the mountain, months of anticipation and really, years of dreaming.

Now here’s the thing, it wasn’t the euphoric moment I had anticipated. I mean, it was incredible, but it wasn’t the moment of catharsis that I had imagined. Or at least not in the way I imagined.

Instead, I saw it, gawked for a minute and then a gloriously unexpected realization came to my fuzzy brain – it’s over! We get to go down now!

I felt relaxed in that moment, satisfied with what I had accomplished, in the pride that the three of us had done it together. And I felt an overwhelming sense of relief.

I thought of how glorious that first shower back at the lodge would feel. But that’s where my brain got ahead of reality.

First, we had to take pictures of this amazing place and snap a gals photo with the sign and our Ducks shirts – those tee shirts that were buried under so many layers of jackets. Instantly though, we knew we had a problem. Our hands were so cold that we couldn’t move our fingers, like at all.

I mean, I could only focus my iPhone photos by using my nose to hit the screen (I kid you not. I looked insane, tapping my nose to a phone over and over); there was no way I could grasp my jacket zippers. All dexterity was gone.

Thankfully, yet again our super-human guides came to our rescue. Props to Frank for dutifully unzipping 3-4 jackets (each), snapping some photos (dude wasn’t even wearing gloves during the climb. Seriously?!) and then zipping us all back up.

We smiled the best we could through our monstrous condition. (Bobbi’s face to the far right sums up how we felt – fighting for happiness through pain, discomfort and exhaustion.)

We were on the summit less than 10 minutes, before we began bounding down the mountain thanks to another inexplicable burst of energy. It was 9:30am.

On the way back down to Stella Point we passed another group of climbers in our team – they looked beat. One guy in particular could barely hold his head up, his feet dragged in an unnatural way. But we were all battered to varying degrees and he had several guides with him, so we thought nothing of it really.

My sudden burst of energy was short-lived as the reality of descending quickly came into focus. In the night, as we climbed ever higher, the ground beneath us was frozen, providing surprisingly solid footing even if we couldn’t feel our feet.

Now I could feel my feet, but the sun had thawed the ground; no longer solid it was a 4,000-foot wall of dirt and loose rocks. It was slippery, treacherous, and steep as fuck.

Every step turned into a slide and soon we were half-skiing down this damn mountain. That may sound potentially fun, but not when you’re physically and mentally fatigued. And not when the dirt sends clouds of dust into the air for you to choke on; to dry out your eyes. And not when this form of pseudo-skiing was wreaking havoc on your knees and smashing your toes into the front of your boots.

These were probably the most dangerous hours of our entire time on the mountain.

I had long ago handed my pack over for a guide to carry (everyone had) so I could focus on not dying. Problem was, that guide was much further down the dirt slope than I was and so too was my water.

As the hours stretched on and the distance between hikers grew wider, my throat became sand paper; raw from the dust and lack of moisture.

I hadn’t had water or liquid of any kind since the summit and I was desperate for it. I would love to say that that was the only thing I could think about, my sole focus (crushing as it was) but I had bigger problems.

My feet were in a loosing battle with the mountain. Every time they made contact with the steep angle of the slide, a dagger of pain shot into my toes, up my legs and caused my face to contort in what I’m sure were the most unattractive grimaces ever made. I honestly didn’t think I could take another step, and then I would take another step and the pain would spike all over again.

Annie and Bobbi were getting farther and farther ahead, each of us in our own personal hell. I simply gave up trying to catch up to them; I was just trying not to fall over, to make sure my toes didn’t fall off. Because that’s exactly what it felt like was happening.

Between the pain, the dust, the exhaustion and the now the very evident dehydration, I felt delirious. When the path finally began to level out, my walk was slow, labored and ugly. In fact, everything was ugly at this point. Every damn thing about me.

I hobbled into camp and was met by an exuberantly cheery porter, wide smile on his face. He congratulated me on making it and handed me a plastic cup full of mango juice, “drink dada (sister)!”

“Water?” I croaked desperately. I had never been so single-mindedly focused on anything.

“No dada, drink juice!” he replied in a sing-songy tone.

I burst into tears. Like full on toddler-tantrum-style tears. I would have thrown myself into a pile on the ground and screamed, but I simply didn’t have the energy for that.

Now, I know that the porter had my best interests at heart and that the mango juice would give me much needed sugars since my body had been physically punished for 13+ hours, but I couldn’t help it. The lump in my throat was too big and I had no control over my reaction.

My little standoff lasted maybe :30 seconds before I just chugged the mango juice. It was better than nothing, right? And like magic, water was then given to me.

I had behaved like a child and was treated like one. I was reminded of my mother forcing me to eat my vegetables before allowing me to have dessert, the eternal parent/child negotiation.

I cannot tell you how silly and awful I felt about the tears – but I was a broken person in the moment. A broken person with no control over anything anymore.

Annie and Bobbi watched the whole fiasco. I couldn’t tell if they were more concerned or horrified or entertained. But that’s the great thing about traveling with your best friends; these women have already seen me at my absolute worst, a complete breakdown on a mountain is nothing compared to what they’ve seen.

And speaking of being at your worst, here we finally got a good look at each other. We were mountain monsters. Battered, wind burned, sunburned, wrecked monsters.

I crumpled to the ground in front of my tent and dragged myself inside before slowly and excruciatingly taking my boots off. To my utter surprise, my toes were still intact and weren’t even bloody. They were however, bright red, swollen and brought new tears to my eyes when I touched them.

I lay down and thought about what I had just done. Thought about what was still to come – an hour-long nap and then five more hours of hiking to get to our camp for the night. I started to panic about how the fuck I would possibly put my boots back on and hike another minute, let alone another five hours!

But before my mind could get to the brutal logistics of what lay ahead, I drifted off into the involuntary unconsciousness of sleep.

Wow. Sounds like an unbelievable, and unbelievably hard experience, all in one. Great writing and details!

Thanks Jason! It was one of the craziest days – unbelievable in nearly every way.

Loved reading this Kelly. You are an amazing photographer and writer. What an experience!!

Aw, Bea, you’re the sweetest! I’m so glad you enjoyed it 😀

Being a resident in the country, the pictures albeit too nice and thrilling tend to show me the imminent depletion of snow on that beauty. I was at the summit twice 1998 and 2006, finding lesser snow the second visit, both levels were pretty much higher that what I am seeing here, Gilman’s Point, Stella Point and Uhuru all had tiny glaciers and snow by them. Sad to see what we(human beings) are doing to this globe.

Wow – summiting twice? That’s impressive, congratulations! Our guides did mention to us that the glacier at the top is significantly smaller than it used to be. It’s so unfortunate, but I’m glad you got to see it years ago in all its glory.